Glaciers of Idaho

|

||

|

This cirque on the north face of Borah Peak is thought to be the location of Idaho’s last glacier. (Bruce Otto, 1975) |

Welcome to the Glaciers of Idaho webpage. Idaho was at one time affected by an ice sheet and numerous alpine glaciers. Today it is doubtful that any true glaciers remain. Perennial snowfields and periglacial features such as rock glaciers can be found in several ranges in the central part of the state.

Table of Contents

Glacier Extent

|

Figure 1: MODIS image (July, 12, 2004) showing regions of Idaho that contain permanent bodies of snow or ice identified on USGS topographic maps. |

|

Idaho has 208 glaciers and perennial snowfields, covering 2.6 km2, of which 202 are found in the Sawtooth Range in central Idaho. The remaining six are found in the Seven Devils Mountains. There are no officially named glaciers in Idaho, based on the US Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System. Most of these features appear to be perennial snowfields based on interpretation from reconnaissance using National Agriculture Imagery Program (NAIP) images acquired in 2004. A few snowfields appear upslope of moraines, but none exhibit crevasses or other clues indicative of movement. Few scientific investigations of perennial snow and ice features in Idaho have been conducted. Note: all statistics here are based on USGS 1:24,000 scale topographic quadrangle maps which are based on mapping photography in 1971 for the Sawtooth Range and 1981 for the Seven Devils. For details see Fountain et al. (2007). Rock glaciers appear to be plentiful in Idaho. A rock glacier is a mass of slowly moving poorly sorted angular boulders and finer material either cemented with interstitial ice, or rocks blanketing a normal alpine glacier. Rock glaciers interpreted from 2004 NAIP reconnaissance are found in the Sawtooth Range (Mijal, 2008), Lemhi Range (Butler, 1988; Johnson et al., 2007), Boulder Mountains, Pioneer Mountains, Boulder Range, and possibly the Beaverhead Mountains and White Cloud Peaks. Many, but not all of these features are mapped as ‘moraine’ on USGS 1:24,000 scale topographic maps. |

Glacial History

|

During the Pleistocene, Idaho was affected by both a continental ice sheet and alpine glaciation. The Purcell Trench Lobe of the Cordilleran Ice Sheet would periodically dam the Clark Fork River at present day Lake Pend Oreille to form glacial Lake Missoula (Bretz et al., 1956). Catastrophic failures of this dam released torrents of water known as the Missoula Floods, which would follow the path of the Columbia River to its mouth at the Pacific Ocean leaving the channeled scablands of eastern Washington (Bretz et al., 1956) and iceberg rafted erratics in the Willamette Valley, Oregon (Minervini et al., 2003). Pleistocene alpine glaciation affected many mountainous areas; in the Sawtooth Range, glaciers left the U-shaped valleys, cirques, horns, and arêtes which contribute to the scenic beauty of this range today. Redfish and Alturas lakes are moraine-dammed lakes formed when glaciers advanced from the Sawtooth into the Stanley Basin (Borgert, 1999). This range was glaciated during the ‘Little Ice Age’ (Mijal, 2008). |

Glaciated Regions

Sawtooth Range |

Seven Devils Mountains |

Sawtooth Range

|

About 202 perennial snow/ice features are found in the Sawtooth Range. These features cover an area totaling 2.5 km2. Rock glaciers can be found in the Sawtooths and tend to be on north or east facing slopes (Mijal, 2008). |

Figure 3: Permanent bodies of snow or ice located within the Sawtooth Range. |

||

Figure 2: Rock Glacier on north side of Glens Peak in the Sawtooth Range. Red line is derived from USGS 1:24,000 scale topographic maps (Mount Everly Quadrangle, 1972) and represents a perennial snow/ice feature. (Photo: NAIP, 2004) |

|||

Back to Glaciated Regions

Back to Contents

Seven Devils Mountains

|

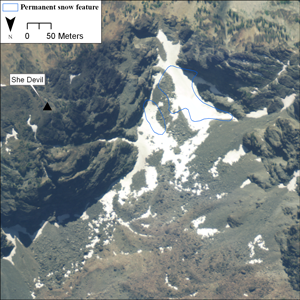

At least six perennial snow features are found in the Seven Devils Mountains. Together, these features cover an area less than 0.1 km2. None of these features appear to show signs of movement. |

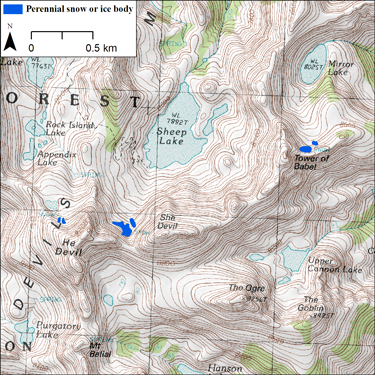

Figure 5: Perennial bodies of snow or ice located within the Seven Devils Mountains. Base map is USGS He Devil Quadrangle released in 1990.

|

|||

|

||||

Back to Glaciated Regions

Back to Contents

Other Regions of Interest

|

||

|

Figure 6: MODIS image (July, 12, 2004) showing regions of Idaho that may contain perennial bodies of snow or ice not identified on USGS topographic maps. |

||

Boulder Mountains |

Lost River Range |

Pioneer Range |

White Cloud Peaks |

Boulder Mountains

|

No perennial snowfields are shown in the Boulder Range on USGS 1:24,000 topographic maps. Kent Peak appears to have a perennial snowfield. A climber’s guide (Lopez, 2000) mentions the presence of a ‘bergschrund’ on its northeast facing slope. |

Figure 7: Kent Peak northeast slopes (2004) as seen from Ryan Peak. (Photographer: Dan Robbins) |

|||

Back to Other Regions of Interest

Back to Contents

Lost River Range

|

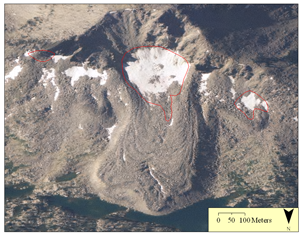

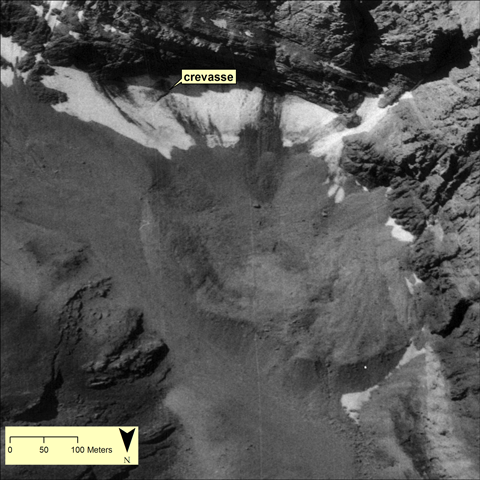

Otto (1977) reports the presence of perhaps the last active alpine glacier in Idaho, a cirque glacier on Borah Peak's north flank. In August, 1975, the glacier was mapped as being about 400 m long and geophysical methods suggest that the maximum thickness was 64 m at this time. The lower third of the glacier was mantled with rock debris from the cirque headwall. The glacier was observed to have firn (the transitional form between snow and ice, indicating multiple years of snow accumulation) in 1974, 1975, and 1976. Crevasse patterns in these years indicate the glacier was active. The USGS 1:24,000 scale Borah Peak Quadrangle (1967) based on aerial photographs taken in 1966 does not show a glacier on Borah Peak. Aerial photos in 1992 (USGS) show the location as being debris-covered glacier. The presence of a crevasse indicates the glacier was still active at that time. The feature in the image on the right is thought to be Idaho's last active glacier (Otto, 1977). |

Figure 9: The southwest portion of the cirque at the head of Rock Creek on the north face of Borah Peak August 11, 1992 (USGS digital orthophotograph). |

||

Figure 8: Photo from fieldwork by Bruce Otto in 1975 showing glacier ice. |

Examination of NAIP vertical aerial photos of 2004 show the development of a melt pond in the lower region of the glacier, which indicates buried ice is present. The location of the crevasse seen in the 1992 image was obscured by seasonal snow. A regular climber of Borah Peak states that "The ice cover in the mid 70s started at the moraine. By 1990 half of this ice was gone." By the autumn of 1990 the entire lower ice field and glacier had completely melted out without a trace (Bob Boyles, climber, written communication, 2009). |

||

Back to Other Regions of Interest

Back to Contents

Pioneer Range

|

No perennial snowfields are mapped in the Pioneer Range; however such features can be seen on north and east facing slopes in aerial photos (NAIP, 2004). |

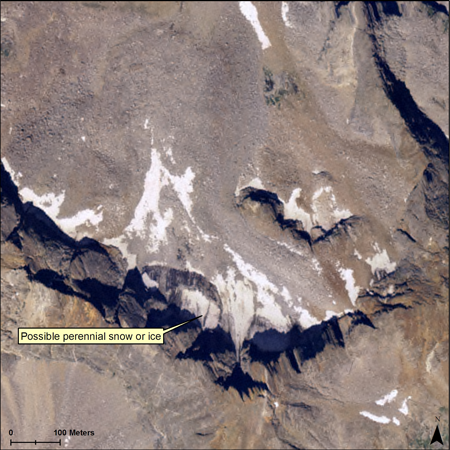

An unnamed peak in the Pioneer Range with what appears to be a small body of perennial snow or ice. (Photo: NAIP 2004) |

Back to Other Regions of Interest

Back to Contents

White Cloud Peaks

|

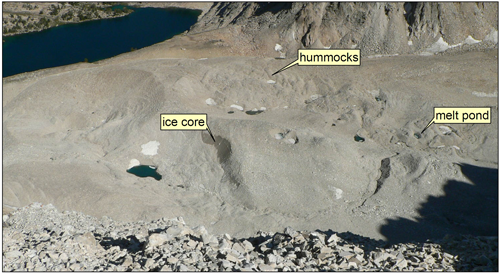

No perennial snowfields are mapped in the White Cloud Peaks. On the east slope of D.O. Lee Peak in the White Cloud Peaks is a region called The Kettles, where hummocky terrain and pools of water suggest stagnant ice is melting beneath a mantle of rocky debris. |

Figure 11: Northeast cirque on D.O. Lee Peak (August, 2005) showing feature that is possibly debris covered stagnant ice. Hummocky topography and melt ponds indicate the presence of melting ice beneath the rocky debris. (Photo by Dan Robbins) |

Back to Other Regions of Interest

Back to Contents

Fun Facts

|

|

Austrian Winter Peas (Texas A&M AgriLIFE) |

Cutthroat Trout. (Pat Clayton-©FishEyeGuyPhotography) |

Acknowledgements

| We wish to thank Mr. Bruce Otto for his generousity in sharing his photographs and reports on the Borah Peak glacier. |

References

|

Borgert, J. A., 1999, Extent and Chronology of Alpine Glaciation in the Alturas Valley, Sawtooth Mountains, Idaho: M.S. Geology, Idaho State University. Bretz, J. H., Smith, H. T. U., and Neff, G. E., 1956, Channeled Scabland of Washington: New data and interpretations: Geological Society of America Bulletin, v. 67, no. 8, p. 957-1049. Butler, D. R., 1988, Neoglacial climatic inferences from rock glaciers and protalus ramparts, southern Lemhi Mountains, Idaho: Physical Geography, v. 9, no. 1, p. 71-80. Crone, A. J., Machette, M. N., Bonilla, M. G., Lienkaemper, J. J., Pierce, K. L., Scott, W. E., and Bucknam, R. C., 1984, Characteristics of surface faulting accompanying the Borah Peak earthquake, central Idaho: Proceedings from Workshop XXVIII on the Borah Peak, Idaho earthquake. U.S. Geological Survey Open File Report 85-290, v. A, p. 43–58. Fountain, A. G., Hoffman, M., Jackson, K., Basagic, H. J., Nylen, T. H., and Percy, D., 2007, Digital outlines and topography of the glaciers of the American West: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2006-1340, p. 23. Johnson, B. G., Thackray, G. D., and Van Kirk, R., 2007, The effect of topography, latitude, and lithology on rock glacier distribution in the Lemhi Range, central Idaho, USA: Geomorphology, v. 91, no. 1, p. 38. Lopez, T., 2000, Idaho, a climbing guide: climbs, scrambles, and hikes: Mountaineers Press, Seattle, WA. 397 p. Mijal, B., 2008, Holocene and latest Pleistocene glaciation in the Sawtooth Mountains, central Idaho: M.S. Geology, Western Washington University. Minervini, J. M., O'Connor, J. E., and Wells, R. E., 2003, Maps showing inundation depths, ice-rafted erratics, and sedimentary facies of late Pleistocene Missoula floods in the Willamette Valley, Oregon: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 03-408. Otto, B. R., 1977, An active alpine glacier, Lost River Range, Idaho: Northwest Geology, v. 6, no. 2, p. 85-87. |

Created by Charles Cannon

Last updated 24 Aug 2011